The media has long relied on experts to help verify, back up and explain concepts to their readers.

From ‘how to bleed a radiator’ to ‘the best star sign for your puppy’, journalists rely on specialists for vital context and information around specific topics.

And, in the last five years, a combination of limited seasonal opportunities, shrinking space in the SERPs and the unregulated catalyst of AI tools has seen an explosion in the number of expert-led articles.

Our research, conducted in collaboration with the Press Gazette, can now reveal the effect this has had on the wider media landscape. So just how many unverifiable experts are being relied on by the UK press in 2025?

What do we mean by ‘Untraceable Experts’?

To get our initial dataset, we focused our approach on articles that included the “expert” keyword within phrases typically used in PR-led stories (e.g., “expert reveals”, “expert warns” and “expert recommends”). This format is the most repeatable for the press and also the easiest to spoof. As seen in the recent exposé of MyJobQuote in our first collaboration with Press Gazette.

Once we had found at least 50 for each publication, we manually searched for evidence that the featured expert exists. Starting first with the company they are representing through author or profile pages, next in relevant trade spaces and review sites and finally through social media profiles.

We considered an expert untraceable if they failed to appear in any of the three areas we checked, or if we did find them, but their online presence showed no evidence of the expertise they claimed. This manual process was the only way to ensure we had exhausted all possibilities with human-led sense-checking rather than automation.

One in three (33%) experts quoted in PR-led tabloid articles cannot be verified to exist

Among the further markers of identification, over a third (35%) have no public photo, 44% have no LinkedIn profile, and more than half aren’t mentioned on the site of the brand that claims to represent them.

Although this doesn’t guarantee that the names used in the pieces don’t exist, it does raise fair questions about the validity of their advice. Furthermore, some of the examples we found were verifiable as people but had completely different job titles than those claimed in the piece, and there was no further evidence that they had qualifications beyond their professional experience. Often, they are marketers, PR professionals, or senior leadership within unrelated companies.

Though surprising. This is not a new problem; NeoMam’s Managing Director, Alex Cassidy, alerted the industry to this situation last year on the Digital PR Podcast:

“You could argue that there are a lot of PR agencies that have been writing comments on behalf of the experts for a long time (which is a more acceptable ‘brown paper bag’ than faking them outright), but we’ve gone from only experts providing the advice to now an AI doing it.

Which is why utilising personalities in reactive is going to become so much more important. Because journalists are worried about them using experts that don’t exist. So they’re going to need to ask is this person real? Can I actually rely on them for comment?”

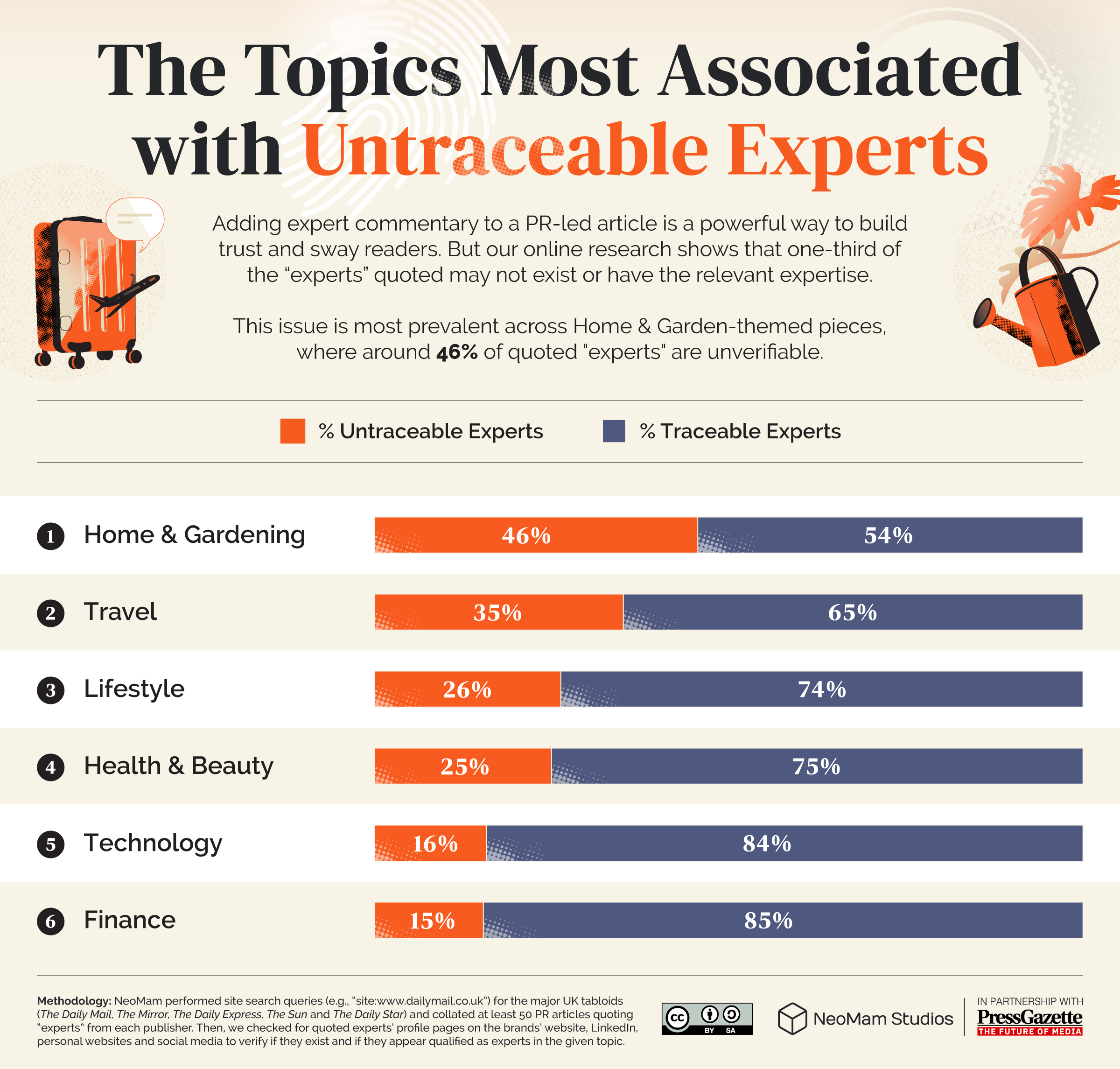

Nearly half (46%) of the experts quoted in Home & Gardening sections of tabloids cannot be verified

Ranking the untraceable experts by section in the UK’s major tabloids, Home & Gardening stands out by a considerable margin. Nearly half of the experts quoted in the PR-led articles we found, 46%, could not be traced or verified.

Coming in second is Travel, with more than a third of quoted experts in this section (35%) lacking any confirmable credentials or online presence.

Further down the list, we see Finance, which records a smaller but still significant proportion (15%) of quoted experts who could not be verified.

Together, these rankings highlight a consistent issue across different beats: a substantial share of expert voices used to reinforce PR-driven stories cannot be reliably connected to real-world qualifications or identities.

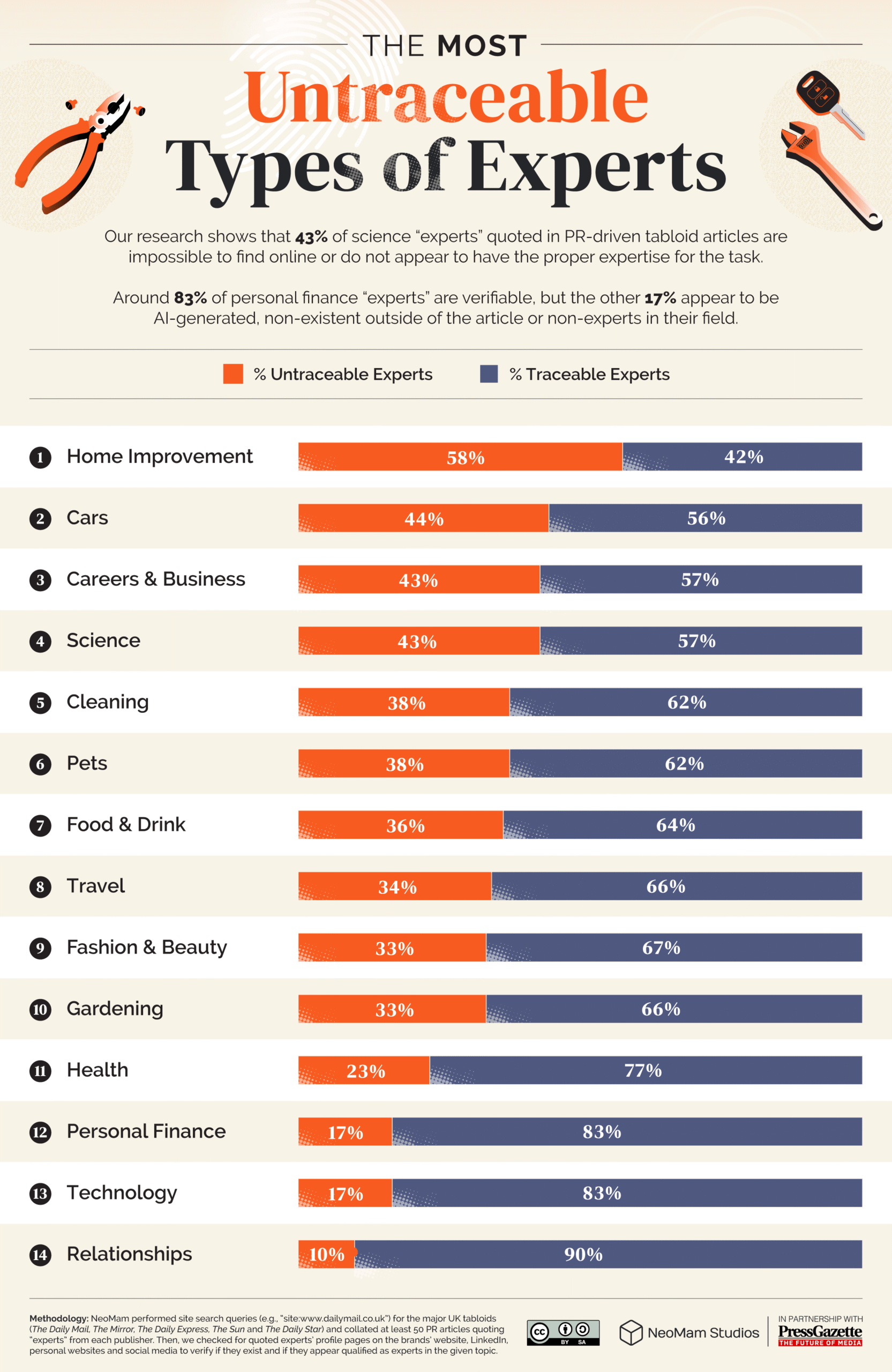

57% of Home Improvement experts in UK press are unverifiable

Among all the topic areas where tabloids quote expert commentary, Home Improvement stands out as the most problematic. Over half of the experts (58%) who provided DIY or renovation advice could not be found online, making it the least traceable category in the dataset.

The next two categories show a similar pattern, though at slightly lower levels. In Cars, more than two in five quoted experts (44%) had no digital footprint, despite routinely being used to support automotive trends, cost claims or safety commentary in PR-led stories. And in Careers & Business, 43% of experts could not be confirmed to exist or to possess the expertise they were cited for.

Together, these top three categories reveal a clear trend: some of the most practical, advice-driven areas of tabloid reporting are among the most reliant on experts who leave no trace beyond the articles in which they appear. The fact that these areas also overlap with hobbyism makes the danger of people taking this dubious advice clear.

The future of journalism and expertise

Rob Waugh, whose journalism has been helping to expose the rise in fake experts and who collaborated with us on this data, said the following:

“This is not the first ‘fake experts’ story I have covered this year, but it is by far and away the largest and the most shameless. The sheer scale of it is absolutely staggering: it hit home to me very powerfully as I manually entered data and there were so many stories that it took me almost two entire days. I actually think there are a fair number we missed, as I entered it I kept finding new experts, new advice, new lies.

This is industrial-scale deception, and while it might seem that it is restricted to relatively low-stakes topics, experts associated with MyJobQuote have given advice on subjects including gas safety, which can kill. This sort of scam pollutes the information landscape, makes the job harder for both journalists and legitimate PRs, and devalues publications – including specialist titles – where trust should be key.

So where does the problem lie?When I first covered this topic, I thought this was an AI issue, with AI accelerating the process by which fake content, fake personas and fake advice can be generated. And I thought it was a relatively isolated scam perpetrated by a few rogue SEO guys misusing the toolkit of digital PR. But the scale of this shows that this is a major issue, and while AI is enabling it, I’m increasingly of the opinion that a lot of the problem comes from the newsrooms that uncritically run content like this.

The 10-stories-a-day mentality of newsrooms where junior journalists are treated like data-entry clerks contributes to this, and I also feel that some senior staff must have known the stories were low-quality and deceptive. Most adults have dealt with pest control, for example, and should know that when pest controllers come round to deal with rat infestations, they do not arrive with a bag of onions and essential oils.”

| Press Gazette: Read Rob Waugh’s journalism on the subject here. |

Journalists will need to continue to use experts as part of their journalism, and PRs will continue to use this method to gain coverage for their clients.

But with the unabated rise of AI, the tech has progressed to the point where photos, videos and even press appearances aren’t enough to prove that a person exists. With more newsrooms leaning on AI as a way to vet articles, this could also compound the problem on both sides of the media aisle.

In the short term, sense-checking, increased process checks from journalists and reporting of bad actors and suspected fakes to press regulators like IPSO.

In the longer term, this should mean increased regulation, thorough reassessment of standards across the aisle from journalists and PRs and a focus on human-led content that ensures that.

| Methodology: We narrowed our approach by focusing on articles that included the “expert” keyword within phrases typically used in the PR-led stories (e.g., “expert reveals”, “expert warns” and “expert recommends”). This format is the most repeatable for press and also the easiest to fake. Once we had found at least 50 for each publication, we manually searched for evidence that the featured expert exists. Starting first with the company they are representing through author or profile pages, next in relevant trade spaces and review sites, and finally through social media profiles (like LinkedIn, Instagram, or Facebook) and personal websites. We considered an expert untraceable if they failed to appear in any of the three areas we checked, or if we did find them but their online presence showed no evidence of the expertise they claimed. For example, someone working as a digital marketer while presenting themselves as a gardening expert. However, a different job title alone did not disqualify them. If an individual had changed careers but still had verifiable proof of expertise in the relevant field, such as a degree or previous professional experience, they were still considered traceable. This manual process was the only way to ensure we had exhausted all possibilities with human-led sense-checking rather than automation. Note: We made tabloid media our focus because the PR-led expert tips format is primarily used by those publications. |